The Northwest Passage – a water route through the islands of northern Canada connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans – a treasure that explorers had sought for centuries.

The quest began as a search for a shorter shipping route between Europe and Asia. But, with each ship and life lost during the 300 year search, explorers seeking the Northwest Passage were also on a hunt for glory.

The Early Explorers

The Inuit were the first explorers of the Arctic. Most of their travels are undocumented, but the Inuit and other First Nations groups are considered to be the discoverers of the Northwest Passage.

In the 16th century, Europeans set their sights on finding a shorter shipping route to Asia through the northern waterways. And over time, with each adventurer, the Northwest Passage was uncovered bit by bit, link by link.

In the 1570s, British explorer Martin Frobisher was one of the first Europeans to try to find the passage. Between 1576 and 1578, he took a small fleet to the northern waters. However, he didn’t make it past the inlet that now bears his name.

The most infamous explorer was Sir John Franklin

By order of the Queen, the British explorer took two ships to search for the elusive Northwest Passage from 1845 to 1848. He took a crew of 134 men and three years’ worth of supplies – including a piano, fine crystal and 1,200 books. Wives and girlfriends of crewmembers confidently sent their letters to China.

The explorers never returned.

The disappearance provoked what some say was the most expensive search-and-rescue mission ever mounted. Between 1848 and 1859, as many as 40 ships and more than 2,000 men searched for Franklin’s fleet. In 1859, searchers found artifacts and bodies on King William Island. They found two documents that indicated the ships had become frozen in the ice. The notes also indicated that Franklin died on the ship in 1847. Survivors abandoned the vessel the year after, but all died trying to reach the mainland.

Scientists later dug up crewmembers bodies and discovered that lead poisoning from the soldering on tins of canned food may have been a factor in their deaths, and would have had an effect on their physical and mental stability. Even more gruesome, analysis of the crewmembers’ remains pointed to cannibalism.

It wasn’t all in vain – the links found during Franklin’s doomed expedition and subsequent search parties helped map out the Northwest Passage.

Roald Amundsen

The full route wouldn’t be travelled until 1903, when Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen used a 21-metre fishing boat the Gjoa to travel its entire length. During his crossing Amundsen had many encounters with Inuit communities. The lessons he learnt from them helped with his Arctic voyage and also with his subsequent success in being the first person to reach the South Pole. At various points along the way, he reportedly had to wait for months on end for the ice to melt enough so his vessel could pass through.

From 1940 to 1942, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police schooner St. Roch navigated the passage from west to east for the first time as a show of Canadian sovereignty over the North. At the end of its journey, the St. Roch turned around and went back, making it the first vessel to complete the journey in both directions.

The Northwest Passage is coveted again

Perhaps the sacrifices were worth it.

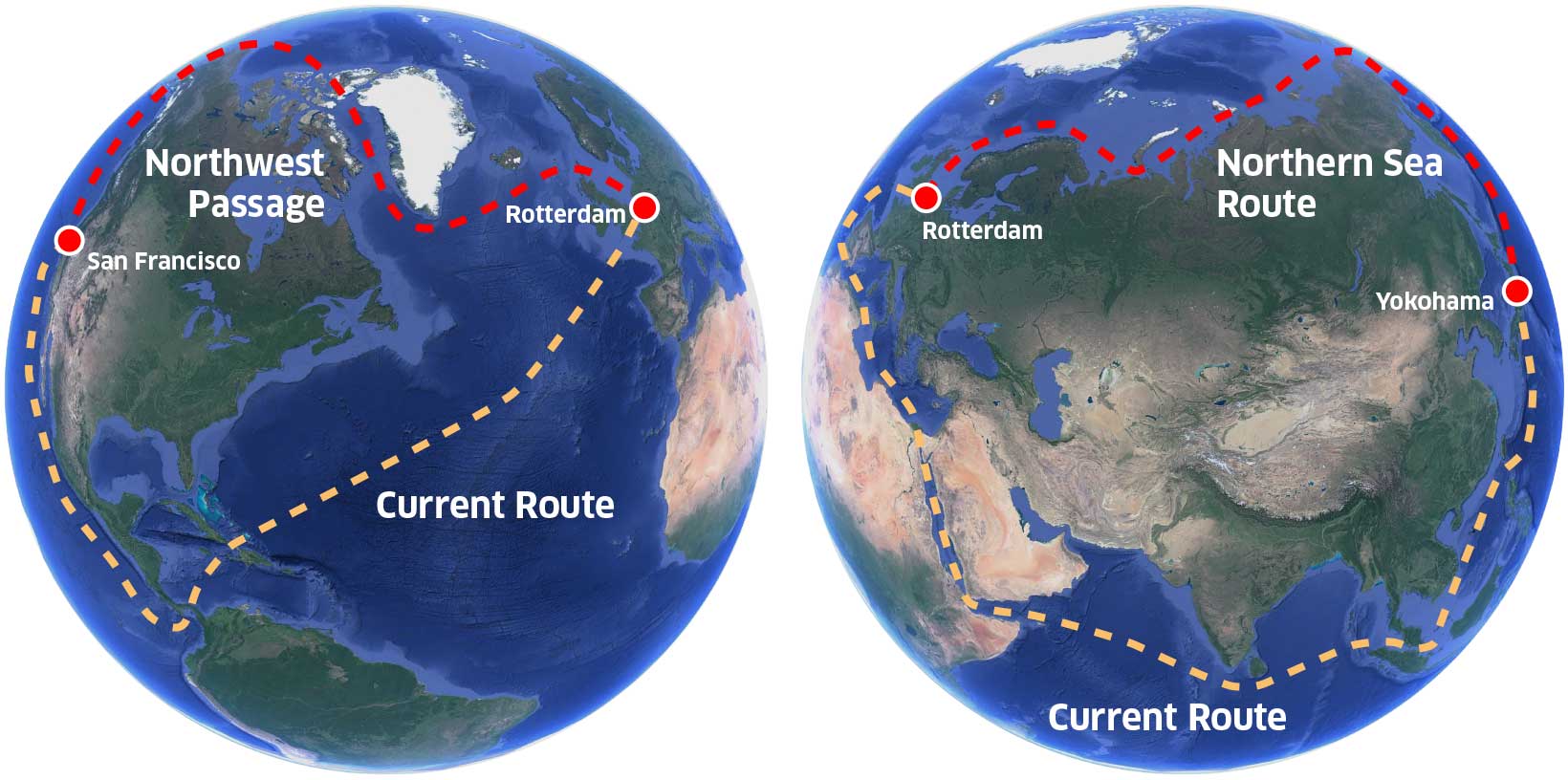

The Northwest Passage is 7,000 kilometres shorter than the current shipping route through the Panama Canal. That’s about two weeks saved in travelling time. From London to Tokyo via the canal, the distance is about 23,000 kilometres. Travelling east through the Suez Canal is also longer at 21,000 kilometres. The route through the passage is just 16,000 kilometres.

However, it’s rarely used since it is frozen over for most of the year, making it impossible for all but the most heavily reinforced icebreakers to make it through.

But as scientists speculate that the Arctic ice is melting, the passage is becoming a coveted shipping route. And the issue of whether the Northwest Passage is an internal waterway, and therefore Canada’s, or an international waterway open to all remains murky.

In 1969, an American tanker, the S.S. Manhattan, made a voyage through the Northwest Passage without asking Canada’s permission. It was an attempt to prove the passage was a viable route for shipping oil.

Canada didn’t try to stop it, but granted unsolicited permission and provided a Canadian icebreaker to escort the S.S. Manhattan.

In 1970, the ship made another trip through the passage. In the end, Canada imposed environmental regulations on trips through the passage, but the issue of who controlled the waters was not resolved.

In 1985, the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Sea transited the passage – without asking the Canadian government for permission. The political fallout over what was considered the most direct challenge to Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic led to the signing of the Arctic Co-operation Agreement in 1988 by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and U.S. President Ronald Reagan. The document states that the U.S. would refrain from sending icebreakers through the Northwest Passage without Canada’s consent; in turn, Canada would always give consent. However, the issue of whether the waters were international or internal was again left unresolved.

Global warming opens up the waterways

In recent years, scientists have been urging the Canadian government to take more steps to stake its claim on the North.

Jacinthe Lacroix, senior science adviser for Environment Canada, says the ice in Canada’s Arctic has shrunk 32 per cent since the 1960s. As well, she says, global warming has raised the temperature in Canada’s northern archipelago by 1.2 degrees in the last century – twice the average rate the temperature is rising worldwide. Each year, the ice shrinks by 70,000 sq km, the equivalent of Lake Superior, she says.

“Some studies show, if it continues to melt at that speed, by the end of the century, there could be no more summer ice in the Arctic,” Lacroix said.

Other scientists have echoed these findings, but there is disagreement on the amount of time involved.

In 2004, André Rochon, chief scientist on Canada’s Amundsen research icebreaker, said climate change could make the route almost ice-free within 50 years, clearing the way for countries and companies to use the waterway. In June 2006, University of British Columbia Prof. Michael Byers said the Northwest Passage would be clear of ice during the summer months in 25 years, and he urged the government to take action.

Corporations worldwide have taken notice, says George Newton of the Arctic Research Commission. In June 2006, he warned that companies had recently invested $4.5 billion in ships that can navigate the ice.

Foreign Minister Peter MacKay has said he’s aware that climate change was melting Arctic ice, and that more personnel are required to protect the Northwest Passage.

However, he has dismissed the prospect of foreign ships rushing to use the route.

“These waters are still very dangerous in terms of their navigation,” MacKay said. “Free-floating ice is also a hazard. I would suggest in the short term you are not going to see necessarily increased passage there except for Canadian ships.”

Lacroix agrees, saying that even if the passage were free from ice during the summer, large chunks of ice would drift down from the Arctic. “It will be very hazardous to do any shipping in this region,” she said.

Canada strengthens its defences

However, the frozen or floating ice won’t stop submarines from passing through Canada’s archipelago. There have been reports that many countries secretly send their subs through the passage – and Canada doesn’t have a system to continuously monitor it.

In the 2006 election, Prime Minister Stephen Harper made a campaign promise to defend Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. He promised to bolster Canada’s presence in the waterway with the addition of three heavy-duty armed icebreakers. He also planned to set up a network of underwater sensors to listen for foreign vessels, and put aircraft and unmanned drones in the skies over the North. The total cost of the Arctic commitments made by the Conservatives is about $5.3 billion over five years.

In August 2006, for the first time in more than a generation, the Canadian Navy is returning to the Northwest Passage to take a first-hand look at shipping in the North.

The army, navy and air force will be heading into Lancaster Sound, considered to be the east end of the passage. The Aug. 12 -24 voyage will be undertaken by the frigate HMCS Montreal, two smaller coastal defence vessels and six aircraft; 400 soldiers, sailors, air crew, RCMP and Canadian Coast Guard officers will take part.

Observers say it will mark the first time in 30 years that the Forces have executed an operation of this size and this far north.

Rush for Arctic’s resources provokes territorial tussles

Terry Macalister, guardian.co.uk | Wednesday 6 July 2011 12.30 BST

US, Canada, Russia, Denmark and Norway are becoming embroiled in disputes over boundaries on land and at sea

Two nations on opposite sides of the Nato military alliance divide – Russia and Norway – have signed a deal over who owns what in the Barents Sea. But there are plenty of other territorial tussles going on – some between good friends.

The United States and Canada still disagree on the setting of the boundaries in the Beaufort Sea – an area of intense interest to oil drillers.

Similarly, Canada has yet to resolve a dispute with Denmark over the ownership of Hans Island and where the control line should be drawn in the strait between Greenland (whose sovereignty remains with Denmark) and Ellesmere Island.

But of even greater significance in a world of melting ice floes is control of the North West Passage. Canada insists that it has sovereignty over the sea route and therefore must be asked about usage. The US sees it as a potential area of open water which gives it automatic right of passage for its battleships.

Canadians were incensed when Americans drove the reinforced oil tanker Manhattan through the passage in 1969, followed by the icebreaker Polar Sea in 1985, both without asking for Canadian permission.

The Svalbard archipelago, north-west of Norway, is already covered by an international treaty signed in 1920. But that does still not stop friends like Britain and Norway having disagreements over the way the treaty has been interpreted.

Norway has been given sovereignty and responsibility for administering the fishing rights and safeguarding the environment.

But it is also meant to give other signatories to the treaty – Russia, the US, China and the UK – equal rights to exploit Svalbard’s natural resources four miles onto the continental shelf. The problem is that Norway does not regard the archipelago as having its own shelf, leaving scope for conflict. A major oil discovery off Svalbard would undoubtedly trigger a row.

Meanwhile, the US and Russia still have a disagreement over the exact maritime border from the Bering Sea into the Arctic Ocean. A deal was signed with the then-USSR, but Russia has refused to ratify it.

All Arctic nations still have a major disagreement over who owns bits of the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean, most particularly the 1,800km Lomonosov ridge. Claims are being submitted under the Law of the Sea Convention.

- Read Rush for Arctic’s resources provokes territorial tussles in the Guardian.

Geopolitical role play and debate

Use the resources and suggested characters for a role play/debate on conflicts and geopolitical issues in the Arctic.

Canadian politician

Issues to think about:

- Defence of national sovereignty

- Fishing, tax, shipping and smuggling laws

- Cost of mandatory ‘ice-breaker’ ships

Managing Director of an oil company

Issues to think about:

- Potential for collaboration with other national oil firms

- Cost of exploration for oil

- Environmental impact of oil extraction

Politician from a non-Arctic nation

Issues to think about:

- Potential for exploitation of natural resources – nickel, iron ore, phosphate, copper, cobalt

- Benefits of resources to the country

- Cost of mandatory ‘ice-breaker’ ships to move through the frozen water

Cruise company

Issues to think about:

- Potential for tourism

- Consider the Search and Rescue capability of the area being visited

- The infrastructure of the area and the possibility of evacuating a boat safely and quickly

A shipping company

Issues to think about:

- Possibility for new shipping routes (Trans-arctic)

- Impact on transit time and fuel costs

- Development in localised shipping for resource extraction and tourism

- Any environmental impacts

Indigenous community representative (Inuit)

Issues to think about:

- Thawing permafrost impact on infrastructure (buildings, roads and pipelines) in Alaska and Siberia

- Opportunities with industries such as mining and ship building

- Impact on fishing

- Social and economic changes and the importance of maintaining a traditional way of life

Environmental organisation

Issues to think about:

- Environmental impacts both locally and world wide

- How these impacts can be presented to a global audience

- Methods to encourage a more sustainable future