Two fifths of the Arctic is covered by permanent snow and ice that remains frozen throughout the year.

This area is dominated by glacial processes and landforms. Glaciers form when the amount of snow and ice that accumulates in the winter is greater than the amount that melts in the summer. The snow that falls is compressed over hundreds of years until it is transformed into glacier ice.

This is different to sea ice which is mostly formed by the freezing of surface ocean water.

How much do you know about glaciers?

- Test your knowledge with Glacial features dominoes!

A glacier is an open system, with inputs and outputs. If inputs exceeds outputs, the glacier will advance. If outputs exceed inputs, the glacier will retreat.

- What are the inputs and outputs to a glacial system?

- How is climate change altering the dynamic equilibrium between inputs and outputs?

Arctic Glaciers

Glaciers are classified according to their size, shape and location. The Arctic region contains a wide range of glacier types and other types of ice mass, including:

- An ice sheet: the Greenland Ice Sheet is the Arctic’s only ice sheet, covering approximately 1.7 million km2, with an average ice thickness of 1.67 km. If the entire ice sheet melted overnight, it would raise global sea levels by approximately 7 metres.

- Icecaps: Ice caps are smaller than ice sheets, though have similar characteristics in that they completely cover the underlying land in ice and are typically dome shaped.

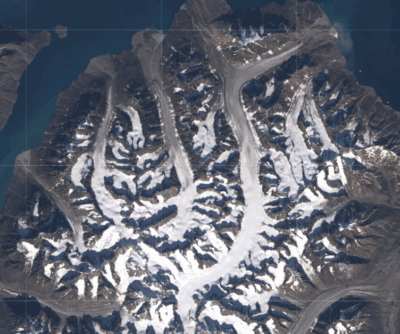

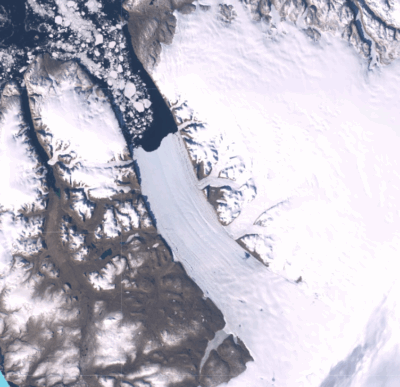

- Valley glaciers: flow outwards from mountain ranges and are typically confined by their valley sides. In some areas of the Arctic (e.g. Alaska) the highest points of the glaciers join together to form large mountain icefields, with the valley glaciers acting as outlet glaciers.

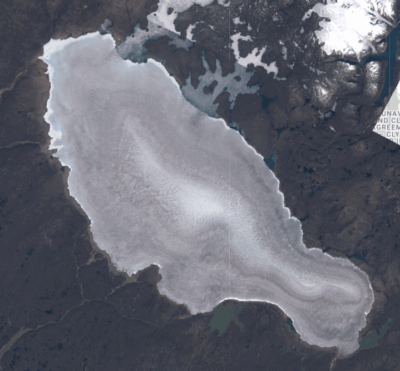

- Piedmont glaciers: glaciers which flow beyond the confines of their valleys and spread out into a lobe as their flow direction is not restricted by the surrounding land.

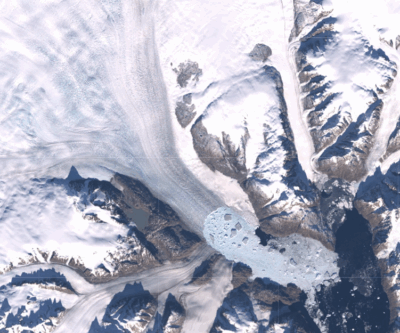

- Tidewater glaciers: those which flow directly into the ocean where they can form icebergs. As they reach the ocean, the bottom of the glacier can be several tens, to several hundred meters below sea level. These glaciers are typically “fast” flowing compared to glaciers that do not flow into the ocean, achieving flow velocities of several hundred metres per year. The fastest flowing glacier globally (Sermeq Kujalleq*, west Greenland) flows at a velocity of between 12 and 14 km per year.

- Ice shelves: is where a glacier flows into the ocean and begins to float, forming a floating tongue of ice. In the Arctic ice shelves only exist in the northern parts of Greenland and are capable of producing city sized icebergs when ice breaks off them.

Find out more about glaciers

- Use the images of the different types of glacier and locate them on a map of the Arctic.

- Add a summary of how they are different from each other on the map as an annotation.

Sea Ice

Sea ice is quite different from glacier ice. It forms when ocean water freezes, often with snow settling on top. Sometimes, it also includes icebergs that have broken off from glaciers that reach the sea, known as tidewater glaciers.

In the Arctic, the amount of sea ice changes a lot throughout the year. It usually reaches its maximum size in March and its minimum in September.

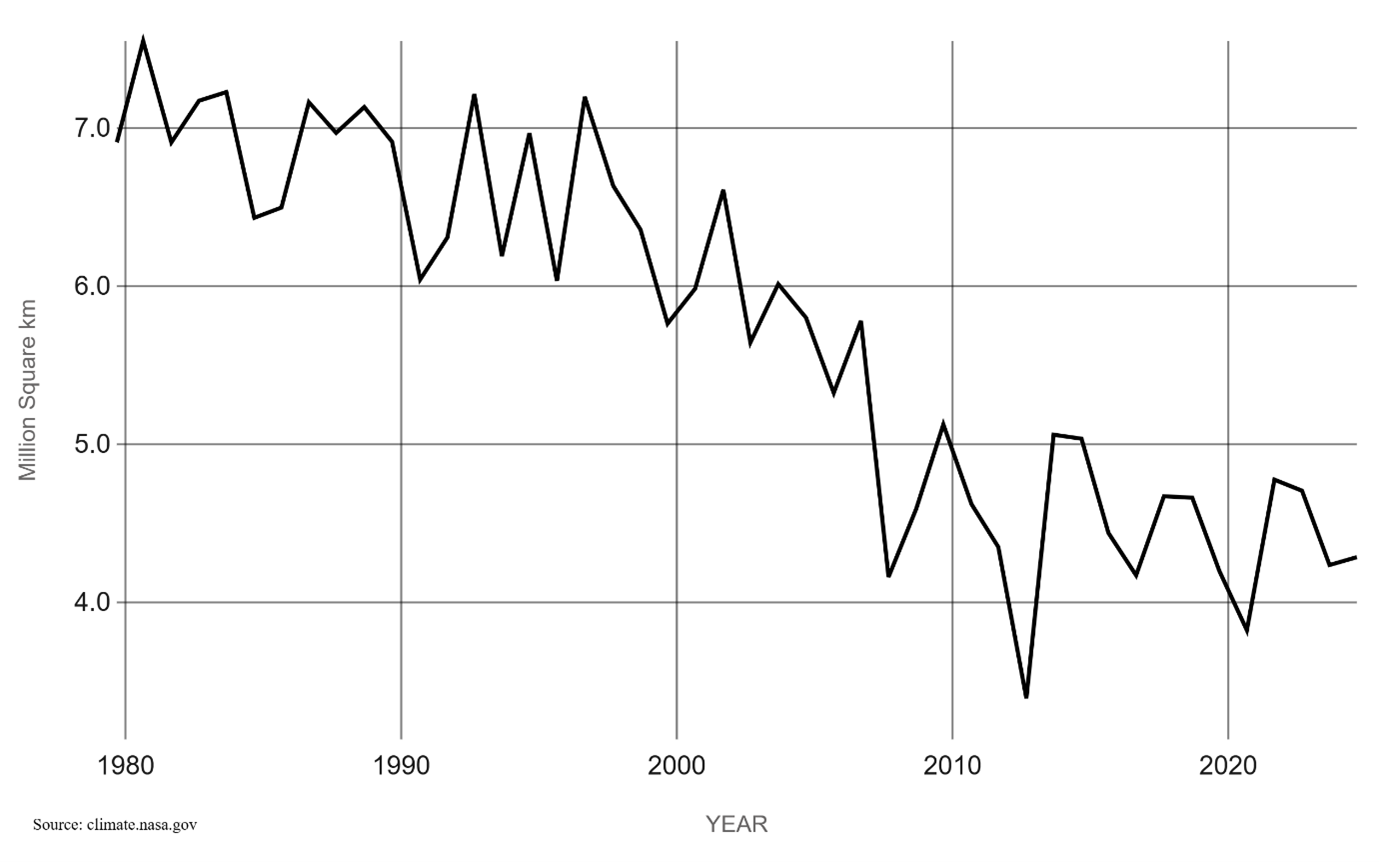

Since 1979, satellites have been used to measure sea ice coverage. Over time, the amount of ice left at the end of summer has dropped by more than 3 million square kilometres. The most dramatic loss happened in the early 2000s, though the rate has slowed a bit since 2007.

Even so, there’s been a big drop in thick, long-lasting “multi-year” ice, while the amount of younger, thinner “first-year” ice has increased. This shows that the Arctic’s ice is not just shrinking, but also getting weaker overall.