Pollution is a real threat to the people and wildlife living in the Arctic.

The Arctic is a wild, remote, sparsely populated region, with little industry. Nevertheless, pollution is a real threat to the people and wildlife living there. There is much current attention in the media on the threat of plastic pollution to marine environments, but first we will consider chemical pollution in the Arctic.

Chemicals

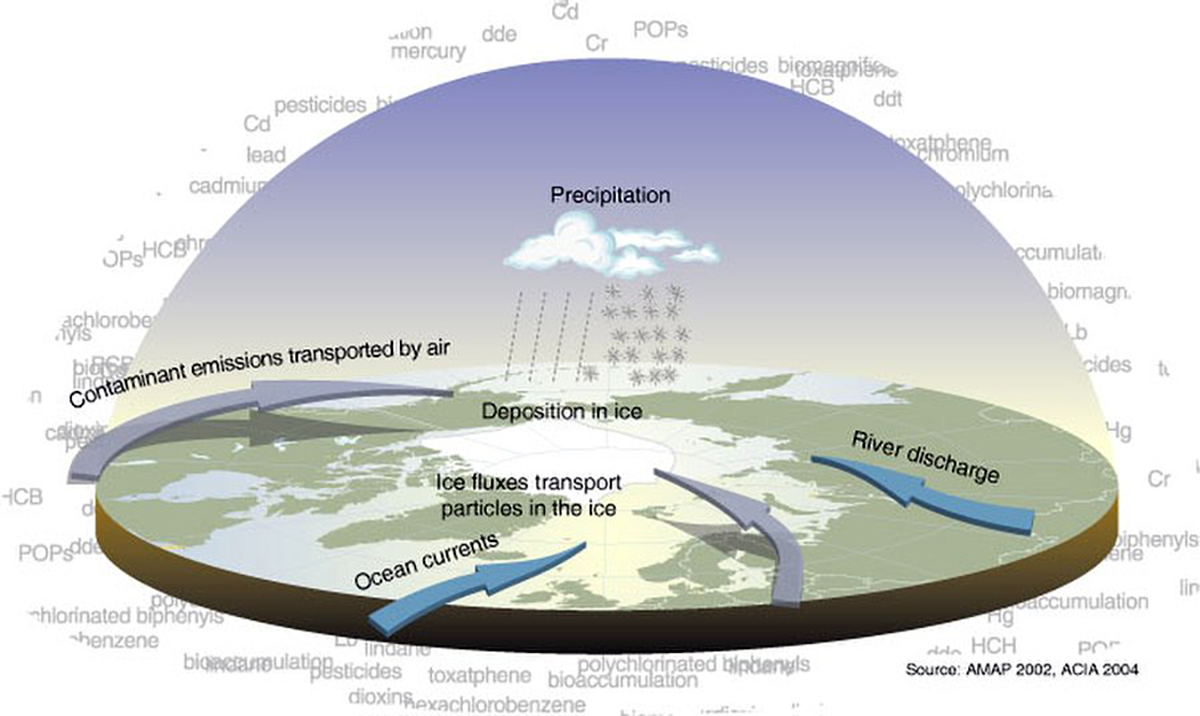

The Arctic Ocean basin acts like a reservoir or ‘sink’ for industrial and agricultural chemicals from Europe, Asia and even further afield which are transported there in the air and ocean currents. The cold temperatures and ice bound environment trap the toxics in the ground, air, water and ice where they degrade extremely slowly. In the summer when the ice melts, the toxins get washed into the sea and rivers.

The main contaminants in the Arctic region are heavy metals, such as mercury and lead, and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as DDT, PCBs and dioxins, which evaporate into the air but are slow to degrade. These toxic materials bioaccumulate in the food chain, passing from planktonic micro-organisms to the fish that eat them, and then on to larger wildlife. As they eat contaminated prey, animals at the top of the food chain, such as polar bears, seals and whales, store more and more toxins in their fatty tissue and organs.

Indigenous people living in the Arctic region who hunt large predators as part of a traditional diet once considered healthy and nutritious are also exposed to toxins in the food they eat. The toxins can affect human development, reproduction, hormone function and weaken the immune system. Polar bear is one of the most contaminated species in the Arctic region and research has found that the Inuit of Canada and Greenland, who hunt polar bear, have higher levels of contaminants in their blood and breast milk than people from the southern regions of these countries.

In 2016 the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) published a report into current chemicals of concern in the Arctic region, including their potential impact on indigenous populations. They concluded that although the accumulation of some POPs has slowed due to global regulations on the use of these chemicals, new chemicals are constantly emerging and research is needed to understand the effects of these on people and wildlife.

Plastics

The world produces 300 million tonnes of plastic every year. 40% of this is for single use items such as carrier bags and plastic drinking bottles, and as a result of the way we dispose of these items, 8 million tonnes of plastic ends up in our oceans every year. In the same way that chemicals reach the Arctic Ocean, plastic litter is building up in this previously pristine environment too. Much of the plastic is discarded fishing gear, but household litter, food wrapping and bottles have also been discovered, originating from all over Europe and across the Atlantic. This discarded plastic can be particularly devastating for wildlife, as the images in this BBC video clip show.

Recently, researchers have become increasingly concerned about the concentrations of microplastics in the Arctic, particularly in sea ice. Microplastics are pieces of plastic less than 5mm in size that form as a result of the breakdown of larger pieces, or sometimes as microbeads from cosmetics and cleaning products. Microplastics generally float, so they are present in the part of the ocean that freezes seasonally to form sea ice. As a result, there can be high concentrations of microplastics in Arctic sea ice – sometimes over 200 pieces per litre. Due to their size, microplastics are easily consumed or inhaled by sea creatures and in this way, like chemicals, can enter the food chain.

Researchers from the Norwegian Polar Institute are monitoring the impact of microplastics on Arctic wildlife, including on a species of seabird called the northern fulmar. They found a significant increase in the amount of microplastic in the stomachs of these birds between the 1970s and 2013. Further research is needed to investigate the impact on humans of consuming microplastics in fish.

You can read more about plastic waste in the Arctic in this BBC Science article, and about the implications of microplastics in the foodchain on the Marine Litter website.

Impact of increased shipping in the Canadian Arctic

The Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban have been researching the impacts of increased shipping in the Canadian Arctic through noise pollution on marine mammals, atmospheric and marine pollution on wildlife and Inuit communities, and through bringing invasive species into the region.

Click here to find out more.

Pollution solutions

As well as investigating the impacts of chemical and plastic pollution in the Arctic region – and worldwide – time and money is being invested globally in researching potential solutions. Here are some examples of how different countries are trying to reduce their impacts.

The US state of Hawaii has become the first to impose a ban on sunscreen products containing the chemicals oxybenzone and octinoxate. These chemicals are responsible for damage to marine ecosystems and can affect reproduction and behavior in fish. Up to 97% of sunscreen can be washed from a person’s body into the sea while swimming, so the impacts are greatest in highly populated areas, but oxybenzone has also been detected in Arctic sea waters demonstrating the powerful effect of ocean currents. Read more about Hawaii’s sunscreen ban in this Guardian article.

Norway has achieved an impressive 97% plastic bottle recycling rate through its return and refund scheme. Customers are charged a 1 krone surcharge to purchase a drink in a plastic bottle. They receive this money back by returning their bottle to one of over 15,000 automated deposit boxes (“reverse vending machines”) across the country. Drinks manufacturers are encouraged to participate in the deposit scheme through tax incentives. Find out more about the scheme by watching this BBC video.

In January 2018, the UK banned the manufacture of microbeads for use in cosmetics and personal care products. In July 2018, a ban on the sale of products containing microbeads also came into force. This followed the 2015 five pence plastic bag levy which has reduced plastic bag use in the country by 9 million bags.

- How would you solve the problem of plastic in the ocean?

Design a poster

Design a poster for a campaign about Arctic pollution showing:

- Where it comes from

- Who it’s affecting

- What can be done

Useful links

- Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP)

one of the working groups of the Arctic Council, AMAP monitors Arctic pollution and offers scientific advice to Arctic governments on how to deal with the contaminants.

For more information about pollution and Arctic wildlife see:

- www.panda.org

- download the panda.org report: Killing them softly.. Health effects in Arctic wildlife linked to chemical exposure

- The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

- Research at the Norwegian Polar Institute has found that ‘old’ POPS such as DTT and PCBS are decreasing but other chemical toxins or ‘new’ POPS are rising.